氟烷

| |

| |

| 临床资料 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Fluothane |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | FDA专业药物信息 |

| 核准状况 | |

| 给药途径 | 吸入 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 | |

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 药物代谢 | 肝脏 (CYP2E1[3]) |

| 排泄途径 | 肾脏, 呼吸系统 |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 151-67-7 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.270 |

| 化学信息 | |

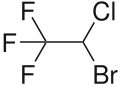

| 化学式 | C2HBrClF3 |

| 摩尔质量 | 197.38 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| 密度 | 1.871 g/cm3 (at 20 °C) |

| 熔点 | −118 °C(−180 °F) |

| 沸点 | 50.2 °C(122.4 °F) |

| |

| |

氟烷(INN:halothane)以商品名称Fluothane于市场上销售,是一种全身麻醉药,[5]可用于诱导以及维持个体于麻醉状态[5]。此药物的优点之一是不会增加唾液分泌,这种特性对于难以插管的患者尤其有用[5]。

使用氟烷的副作用有心律不整、呼吸抑制和肝毒性[5]。有恶性高热家族史的个体不应使用氟烷,此与所有挥发性麻醉药的作用相似[5]。它似乎对有紫质症的个体使用无安全顾虑[6]。目前尚无充分的数据确定个体于怀孕期间使用是否会对胎儿有害,且一般不建议在剖腹产手术中使用此麻醉方式[7]。氟烷是一种手性分子,以消旋混合物的形式使用[8]。

氟烷于1951年由在英国帝国化学工业服务的化学家发现,[9]于1958年在美国取得核准用作医疗用途[2]。它已列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中[10]。

氟烷是温室气体,会导致臭氧层破坏[11][12]。此麻醉药在发达国家中已被较新的麻醉药如七氟醚取代[13]。也不在美国市场上贩售[7]。

医学用途

[编辑]

- 氟烷是一种强效麻醉药,最低肺泡浓度(MAC)为0.74%(MAC是一种麻醉药物在肺泡内的浓度,通常以体积百分比表示。有50%的受试者在MAC浓度时,对手术(疼痛)刺激无运动反应(即不动)。MAC用于比较麻醉药物的强度或效力。)[14]。

- 其血液/气体分配系数为2.4,是一种诱导麻醉和恢复时间适中的药物[15]。

- 氟烷的镇痛效果不佳,肌肉松弛作用属中等程度[16]。

氟烷在麻醉机上的颜色标示为红色(用于易辨识,及作安全警示作用)[17]。

副作用

[编辑]使用氟烷的副作用有心律不整、呼吸抑制和肝毒性[5]。对于紫斑症患者似乎属于安全[5]。目前尚不清楚在怀孕期间的个体使用后是否会对胎儿有害,且一般不建议在剖腹生产手术中使用[7]。成人反复接触氟烷,罕见的有严重的肝损伤案例,发生率约为万分之一。由此产生的症候群称为氟烷性肝炎,为一种免疫过敏性现象,[18]发生原因是由氟烷在肝脏中经氧化反应,代谢成三氟乙酸所致。吸入的氟烷中大约有20%由肝脏代谢,代谢产物经尿液排出体外。

罹患肝炎综合症的死亡率为30%至70%之间[19][20]。对于氟氯会导致肝炎的担忧导致在成人患者中的使用大幅减少,并在1980年代被恩氟醚和地氟醚取代[21]。迄2005年,最常用的挥发性麻醉药是异氟醚、七氟醚和地氟醚。由于儿童发生氟烷性肝炎的风险远低于成人,加上此药物特别适于吸入诱导麻醉,因此在1990年代仍继续在小儿科医疗中使用[22][23]。然而到2000年,由于七氟醚的效果更佳,在小儿科的应用方面大部分已将氟烷取代[24]。

氟烷会让心脏对某些刺激物质(如儿茶酚胺)变得过于敏感,而易引发心律不整,甚至危及生命,当个体体内二氧化碳过多时,这种风险会更高。在牙科手术中,此情况尤需注意[25]。

氟烷是恶性高热的强效诱发因素,与所有强效吸入性麻醉药相似[5]。

氟烷与其他强效吸入性药剂类似,会让子宫平滑肌松弛,可能会增加分娩或终止妊娠(人工流产)期间的出血量[26]。

职业安全

[编辑]医疗人员在工作中可能因吸入废气、皮肤黏膜接触或误食等途径暴露于氟烷[27]。美国国立职业安全与健康研究所(NIOSH)建议工作场所空气中氟烷的60分钟时间加权平均值不应超过2ppm(百万分之一,16.2微克/立方米)[28]。

药理学

[编辑]全身麻醉剂的作用机制尚未完全阐明[29]。氟烷可激活GABAA受体和甘氨酸受体[30][31]。它还是NMDA受体拮抗剂,[31]会抑制烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体(nACh)和电压门控钠通道,[30][32]并激活5-HT3受体和双孔钾通道[30][33]。它不影响AMPA受体或Kainate受体[31]。

化学和物理性质

[编辑]氟烷(2-溴-2-氯-1,1,1-三氟乙烷)是一种高密度、高挥发性、透明、无色及不易燃的液体,具有类似氯仿的甜味。它可微溶于水,而会与各种有机溶剂混溶。氟烷经光和热作用可分解成氟化氢、氯化氢和溴化氢[34]。

| 沸点: | 50.2 °C | (在101.325千帕时) |

| 密度: | 1.871克/立方公分 | (在20 °C时) |

| 分子量: | 197.4道尔顿 (单位) | |

| 蒸气压: | 244毫米汞柱 (32千帕) | (在20 °C时) |

| 288毫米汞柱 (38千帕) | (在24 °C时) | |

| 最低肺泡浓度: | 0.75 | vol % |

| 血液/气体分配系数: | 2.3 | |

| 油气分配系数: | 224 |

化学上,氟烷是一种卤烷(而不像许多其他麻醉剂一般属于醚类)[3]。

合成

[编辑]氟烷的工业合成过程是将三氯乙烯作为起始物质,在三氯化锑催化下,与氟化氢在130°C的条件下反应,生成2-氯-1,1,1-三氟乙烷,接着将得到的2-氯-1,1,1-三氟乙烷在450°C的高温下与溴进行反应,最终得到氟烷。[35]。

相关物质

[编辑]科学家们为减少麻醉药对肝脏的负担,致力寻找分解较慢的麻醉药。其中,氟烷、恩氟烷和异氟烷等卤烷类药物因其较低的肝脏代谢率而成为研究的重点。这些药物在肝脏中的代谢较慢,降低对肝脏的损伤风险。其中异氟烷的代谢几乎可忽略不计,造成肝损伤的报告也极为罕见[36]。虽然恩氟烷的代谢产物较少,但其肝毒性潜能仍存在争议。值得注意的是氟烷和异氟烷的代谢产物 - 三氟乙酸 - 可能导致患者对这些药物产生交叉敏感性[37][38]。

现代麻醉药的主要优势是其血液溶解度较低,麻醉的诱导和恢复速度因而可更快[39]。

历史

[编辑]

氟烷于1951年由在英国帝国化学工业公司工作的化学家C. W. Suckling在威德尼斯实验室成功合成,并于1956年在曼彻斯特由M. Johnstone首次临床使用。许多药理学家和麻醉师最初对这种新药的安全性及有效性存有疑虑。然而氟烷的临床应用推动专业化发展,同时也为英国新成立的国民保健署(NHS)提供良好的技术支持。麻醉师在氟烷的使用中扮演不可或缺的角色,进一步凸显麻醉学在现代医疗体系中的重要性[40]。氟烷最终因为是一种不易燃的全身麻醉药,而取代其他挥发性麻醉药(如三氯乙烯、乙醚和环丙烷)而广为流行。虽然氟烷自1980年代起已被更新的药剂取代,但由于其成本较低,在发展中国家仍受广泛使用[41]。

氟烷自1956年问世起到1980年代之前,曾应用于全球众多的患者身上[42]。其副作用有在高浓度时的心脏抑制、对儿茶酚胺类(如正肾上腺素)的心脏敏感性以及强烈的支气管松弛作用。氟烷对呼吸道缺乏刺激性,使其成为小儿麻醉中常用的吸入诱导剂[43][44]。它在发达国家中已被更新的麻醉药如七氟醚取代[45]。氟烷目前已不在美国贩售[7]。

社会与文化

[编辑]供应

[编辑]氟烷已列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中[10]。药物以挥发性液体的形式提供,容器有30、50、200和250毫升的形式,但在许多发达国家中已由更新的药剂取代[46]。

氟烷是唯一含有溴的吸入性麻醉药,使其具有放射密度不易穿透的特性(X射线不透光性)[47]。它是既无色且气味宜人的液体,但在光照下会不稳定,因此会包装在深色瓶中,并含0.01%的百里酚作为稳定剂[20]。

温室气体

[编辑]氟烷有共价键合的氟原子,在大气窗口(能够穿透地球大气层的电磁波频段)中具吸收作用,因此是种温室气体。但由于其在大气中的寿命较短(估计仅为一年),效力远低于许多碳氟化合物(如氯氟烃和溴氟烃的寿命超过100年)[48]。虽然氟烷的寿命短,但其全球暖化潜势仍是二氧化碳的47倍[49]。据信氟烷对全球暖化的程度微不足道[48]。

臭氧层破坏

[编辑]氟烷是一种会破坏臭氧层的物质,其臭氧层破坏潜势 (ODP) 为1.56,估计它对平流层臭氧层造成破坏的占比为1%[11][12]。

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ Halothane, USP. DailyMed. 2013-09-18 [2022-02-11].

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Fluothane: FDA-Approved Drugs. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [2022-02-12].

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Halothane. DrugBank. DB01159.

- ^ Anvisa. RDC Nº 784 — Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 — Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control]. Diário Oficial da União. 2023 -03-31 (2023-04-04) [2023-08-16]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-03) (巴西葡萄牙语).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 ((World Health Organization)). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR , 编. WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. 2009: 17–8. ISBN 978-92-4-154765-9. hdl:10665/44053

.

.

- ^ James MF, Hift RJ. Porphyrias. British Journal of Anaesthesia. July 2000, 85 (1): 143–53. PMID 10928003. doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.143

.

.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Halothane — FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses. www.drugs.com. June 2005 [2016-12-13]. (原始内容存档于2016-12-21).

- ^ Bricker S. The Anaesthesia Science Viva Book. Cambridge University Press. 17 June 2004: 161. ISBN 978-0-521-68248-0. (原始内容存档于2017-09-10) –通过Google Books.

- ^ Walker SR. Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer. 2012: 109. ISBN 978-94-009-2659-2. (原始内容存档于2017-09-10).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 World Health Organization. The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. hdl:10665/371090

. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Kümmerer K. Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Sources, Fate, Effects and Risks. Springer. 2013: 33. ISBN 978-3-662-09259-0.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Langbein T, Sonntag H, Trapp D, Hoffmann A, Malms W, Röth EP, Mörs V, Zellner R. Volatile anaesthetics and the atmosphere: atmospheric lifetimes and atmospheric effects of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane. British Journal of Anaesthesia. January 1999, 82 (1): 66–73. PMID 10325839. doi:10.1093/bja/82.1.66

.

.

- ^ Yentis SM, Hirsch NP, Ip J. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice 5th. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013: 264. ISBN 978-0-7020-5375-7. (原始内容存档于2017-09-10).

- ^ Lobo SA, Ojeda J, Dua A, Singh K, Lopez J. Minimum Alveolar Concentration. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2022. PMID 30422569. NBK532974.

- ^ Bezuidenhout E. The blood–gas partition coefficient. Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia. November 2020, 1 (3): S8–S11. ISSN 2220-1181. doi:10.36303/SAJAA.2020.26.6.S3.2528

. eISSN 2220-1173.

. eISSN 2220-1173.

- ^ Halothane. Anesthesia General. 31 October 2010. (原始内容存档于16 February 2011).

- ^ Subrahmanyam M, Mohan S. Safety features in anaesthesia machine. Indian J Anaesth. September 2013, 57 (5): 472–480. PMC 3821264

. PMID 24249880. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.120143

. PMID 24249880. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.120143  .

.

- ^ Habibollahi P, Mahboobi N, Esmaeili S, Safari S, Dabbagh A, Alavian SM. Halothane. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. January 2018. PMID 31643481. NBK548151.

- ^ Wark H, Earl J, Chau DD, Overton J. Halothane metabolism in children. British Journal of Anaesthesia. April 1990, 64 (4): 474–481. PMID 2334622. doi:10.1093/bja/64.4.474

.

.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Gyorfi MJ, Kim PY. Halothane Toxicity. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2022. PMID 31424865. NBK545281.

- ^ Hankins DC, Kharasch ED. Determination of the halothane metabolites trifluoroacetic acid and bromide in plasma and urine by ion chromatography. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications. 199-05-097, 692 (2): 413–8. ISSN 0378-4347. PMID 9188831. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(96)00527-0.

- ^ Okuno T, Koutsogiannaki S, Hou L, Bu W, Ohto U, Eckenhoff RG, Yokomizo T, Yuki K. Volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane directly target and attenuate Toll-like receptor 4 system. FASEB Journal. December 2019, 33 (12): 14528–41. PMC 6894077

. PMID 31675483. doi:10.1096/fj.201901570R

. PMID 31675483. doi:10.1096/fj.201901570R  .

.

- ^ Sakai EM, Connolly LA, Klauck JA. Inhalation anesthesiology and volatile liquid anesthetics: focus on isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane. Pharmacotherapy. December 2005, 25 (12): 1773–88. PMID 16305297. S2CID 40873242. doi:10.1592/phco.2005.25.12.1773.

- ^ Patel SS, Goa KL. Sevoflurane. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its clinical use in general anaesthesia. Drugs. April 1996, 51 (4): 658–700. PMID 8706599. S2CID 265731583. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651040-00009.

- ^ Paris ST, Cafferkey M, Tarling M, Hancock P, Yate PM, Flynn PJ. Comparison of sevoflurane and halothane for outpatient dental anaesthesia in children. British Journal of Anaesthesia. September 1997, 79 (3): 280–4. PMID 9389840. doi:10.1093/bja/79.3.280

.

.

- ^ Satuito M, Tom J. Potent Inhalational Anesthetics for Dentistry. Anesthesia Progress. 2016, 63 (1): 42–8; quiz 49. PMC 4751520

. PMID 26866411. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-63.1.42.

. PMID 26866411. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-63.1.42.

- ^ Common Name: Halothene (PDF). Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet (PDF). 1999, 969 (1) –通过New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services.

- ^ Halothane. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. (NIOSH) National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control. [2015-11-03]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-08).

- ^ Perkins B. How does anesthesia work?. Scientific American. 2005-02-07 [2016-06-30].

- ^ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Hemmings HC, Hopkins PM. Foundations of Anesthesia: Basic Sciences for Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2006: 292–. ISBN 978-0-323-03707-5. (原始内容存档于2016-04-30).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Barash P, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan M, Stock CM, Ortega R. Clinical Anesthesia, 7e: Print + Ebook with Multimedia. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2013-02-07: 116–. ISBN 978-1-4698-3027-8. (原始内容存档于2016-06-17).

- ^ Schüttler J, Schwilden H. Modern Anesthetics. Springer. 2008-01-08: 70–. ISBN 978-3-540-74806-9. (原始内容存档于2016-05-01).

- ^ Bowery NG. Allosteric Receptor Modulation in Drug Targeting. CRC Press. 2006-06-19: 143–. ISBN 978-1-4200-1618-5. (原始内容存档于2016-05-10).

- ^ Lewis, R.J. Sax's Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. 9th ed. Volumes 1-3. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996., p. 1761

- ^ Template:Ref patent3

- ^ Halogenated Anesthetics. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. January 2018. PMID 31644158. NBK548851.

- ^ Ma TG, Ling YH, McClure GD, Tseng MT. Effects of trifluoroacetic acid, a halothane metabolite, on C6 glioma cells. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. October 1990, 31 (2): 147–158. Bibcode:1990JTEH...31..147M. PMID 2213926. doi:10.1080/15287399009531444.

- ^ Biermann JS, Rice SA, Fish KJ, Serra MT. Metabolism of halothane in obese Fischer 344 rats. Anesthesiology. September 1989, 71 (3): 431–7. PMID 2774271. doi:10.1097/00000542-198909000-00020

.

.

- ^ Eger EI. The pharmacology of isoflurane. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1984, 56 (Suppl 1): 71S–99S. PMID 6391530.

- ^ Mueller LM. Medicating Anaesthesiology: Pharmaceutical Change, Specialisation and Healthcare Reform in Post-War Britain. Social History of Medicine. March 2021, 34 (4): 1343–65. doi:10.1093/shm/hkaa101.

- ^ Bovill JG. Inhalation Anaesthesia: From Diethyl Ether to Xenon. Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 182. 2008: 121–142. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9. PMID 18175089. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_6.

|issue=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ Niedermeyer E, da Silva FH. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 1156. ISBN 978-0-7817-5126-1. (原始内容存档于2016-05-09).

- ^ Himmel HM. Mechanisms involved in cardiac sensitization by volatile anesthetics: general applicability to halogenated hydrocarbons?. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2008, 38 (9): 773–803. PMID 18941968. S2CID 12906139. doi:10.1080/10408440802237664.

- ^ Chavez CA, Ski CF, Thompson DR. Psychometric properties of the Cardiac Depression Scale: a systematic review. Heart, Lung & Circulation. July 2014, 23 (7): 610–8. PMID 24709392. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.020.

- ^ Yentis SM, Hirsch NP, Ip J. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice 5th. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013: 264. ISBN 978-0-7020-5375-7. (原始内容存档于2017-09-10) (英语).

- ^ National formulary of India 4th. New Delhi, India: Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. 2011: 411.

- ^ Miller AL, Theodore D, Widrich J. Inhalational Anesthetic. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2022. PMID 32119427. NBK554540.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Hodnebrog Ø, Etminan M, Fuglestvedt JS, Marston G, Myhre G, Nielsen CJ, Shine KP, Wallington TJ. Global warming potentials and radiative efficiencies of halocarbons and related compounds: A comprehensive review (PDF). Reviews of Geophysics. 2013-04-24, 51 (2): 300–378. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..300H. doi:10.1002/rog.20013.

- ^ Hodnebrog Ø, Aamaas B, Fuglestvedt JS, Marston G, Myhre G, Nielsen CJ, Sandstad M, Shine KP, Wallington TJ. Updated Global Warming Potentials and Radiative Efficiencies of Halocarbons and Other Weak Atmospheric Absorbers. Reviews of Geophysics. September 2020, 58 (3): e2019RG000691. Bibcode:2020RvGeo..5800691H. PMC 7518032

. PMID 33015672. doi:10.1029/2019RG000691.

. PMID 33015672. doi:10.1029/2019RG000691.