用戶:Hilics3/Sandbox

| 索寧克人 | |

|---|---|

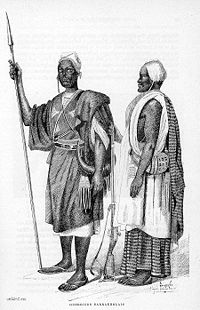

索寧克戰士,1890年 | |

| 總人口 | |

| 約1百萬 (2005) | |

| 分佈地區 | |

| 馬里, 毛里塔尼亞, 塞內加爾, 科特迪瓦, 布基納法索, 加納, 岡比亞, 幾內亞比紹 | |

| 語言 | |

| 索寧克語 | |

| 宗教信仰 | |

| 伊斯蘭教 | |

| 相關族群 | |

| 曼丁戈人, 班巴拉人, Imraguen, Jakhanke |

索寧克人(Soninke,其他拼寫Sarakole、Seraculeh或'Serahuli)是曼德人的一支,他們是Bafour的後裔且與毛里塔尼亞的Imraguen人關係密切。他們說曼德語中的索寧克語.。他們是古老的加納帝國 (公元750~1240年)的締造者。索寧克人的分支包括Maraka和Wangara.

1066年左右,在與來自北方的 穆拉比特王朝 的穆斯林商人接觸後,, 臨近的 Takrur的索寧克貴族成為撒哈拉沙漠以南的西非第一批皈依 伊斯蘭教的人群。加納帝國分裂後,索寧克人流散到馬里、塞內加爾、毛里塔尼亞、岡比亞和幾內亞比紹。這次流散形成了著名的商業民族Wangara,他們的足跡遠至傳統的曼德地區。在加納和布基納法索,Wangara被用來描述城市和村鎮裏的索寧克人。現在,索寧克人約有100萬人。

歷史[編輯]

索寧克人保留着傳統的文化,繼承了締造加納帝國(不要和現代的加納混淆,加納只是使用「加納」這個名字)的祖先們的社會結構。加納帝國在索寧克人的歷史和生活方式中佔有重要地位。 據說[誰說的?]加納帝國的第一位統治者是Dingha Cisse,他被看作是一位半人半神似的的人物。他帶領着他的子民從「東方(可能是馬里抑或現代的塞內加爾)」而來,領導聯盟對抗鄰近的部落和「游牧強盜」。一些人相信經過長期和柏柏爾人的戰鬥之後,Cisse娶了柏柏爾人首領的三個女兒並且締造了一個影響深遠的同盟。

地理[編輯]

索寧克人現在仍然生活在整個西非,但是集中在加納帝國的故土、上塞內加爾河和在Nara和Nioro du Sahel之間的馬里與塞內加爾邊境。在法國的殖民統治下,一些人被鼓勵移民尋找工作,他們在達喀爾和非洲的其他大城市建立了社區。法國的巴黎也有一個龐大且逐漸增長的索寧克人社區。由著名的「Wangara」貿易聯盟領導的貿易網絡,把索寧克人和他們的文化帶到馬里和塞內加爾的大部、毛里塔尼亞南部、布基納法索北部、岡比亞部分地區和幾內亞比紹。Maraka——索寧克商人社區和種植園(集中在馬里城市塞古的北方)——是班巴拉帝國的經濟動力,他們開闢了整個地區的貿易路線。

社會組織與政治[編輯]

The ancient Soninke empire was governed by a powerful emperor who controlled the Trans-Saharan Trade. His power was limited by nobles in charge of the bureaucracy, taxes, army, justice and other duties. The central government of the empire was composed of the emperor and those nobles who can be considered as important advisors. The peripheral courts had some freedom deciding on their interior problems however they were supervised by the imperial court concerning imperial problems as well as the army. In the time of Wagadu there was an emperor at the head of the empire followed by the noble’s families. Even after the decline of the empire the majority of the Soninke families still maintained this hierarchy in their villages. In the Soninke social organization everyone occupies a place. Being king or a smith was not by choice, it was an inherited position. This hierarchy is very important in Soninke culture and it is respected by the Soninke. This structural social organization is divided in three levels. 古代的索寧克帝國由一位強力的君王統治,他掌控着跨撒哈拉沙漠貿易。掌管官僚、稅收、軍隊、司法和其他職責的貴族們限制了他的權力。帝國的中央政府由君王和充當顧問的貴族們組成。

The first class are the ″Hooro″, the free men. They have the highest social rank. The Hooro are the rulers, they have the right to punish and dispense justice. The first class in the 「Hooro」 are the 「tunkalemmu」, the princes. They exercise authority. Only a tunkalemmu」 can become king. It's an inherited position. The next class after the princes, 「tunnkalemmu」, are the 「mangu」. The 「mangu」 are the advisors of the princes. They are their confidants. They act as mediators in conflicts between different classes of 「Hooro」 or free man. The 「mangu」 originate from the 「kuralemme」, warrior class. In times of war the Mangu become heads of the army. The last class of the 「hooro」, free man is the 「modinu」, the priest. Their origin is from the influence of Islam in Soninke society. They dispense justice, and educate the population. They teach them Islam and protect them with prayers. They are very respected for their religious knowledge.

The second level of the Soninke organization is the 「naxamala」 which is also divided in many other classes. The 「naxamala」 are the dependent men. The 「tago」 or blacksmiths occupy the highest position. They make weapons and work tools. They also make jewelry. They are respected for their knowledge with iron. The next class after blacksmith is the carpenter, 「sakko」. They are the friends of the inhabitants of the forest. They are the confidants and the masters of devils. They are important because of their skills and knowledge with wood. The next class is the praise-singer, 「Jaroo」. During ceremonies they are in charge of animation, speaking, and singing. They are the most famous in the 「naxamala」 dependent class . They are the only ones authorized to say anything they want. They are the orators of the society. They tell the history of most important Soninke families. The last class in the 「naxamala」 class is the cobbler, 「Garanko」. They are in charge of making leather shoes, saddles and saber sheaths.

The lowest level of the Soninke social hierarchy are the slaves known as 『komo』. The 「komo」, slaves work for the masters. Their masters had to take care of them but this was not always the case. The slaves have always been the major labor force in Soninke society. The prosperity of Soninke society was due to their dominance in farming. In the past there were more slaves than free-men.

人民和文化[編輯]

婚姻[編輯]

The different Soninke social classes do not marry one another. Free-men do not marry people from the dependent class or slaves. A priest can marry a princess but a prince cannot marry a priestess. 不同社會階層的Soninke彼此不通婚。 Marriage is preceded by an official courtship ritual. If a man likes a woman, he sends his parents to convince the woman's family to give her in marriage. If both families agree, the couple is engaged (i na tamma laga) in a mosque. Each month after the engagement, the man pays the woman's family his contribution (nakhafa) for their food and other spending. Every holiday, such as tabaski, he also gives them meat if he has the means. When both families agree that it is time for the couple to live together, they organize the marriage, called futtu, usually on a Thursday afternoon, and the woman is sent to the man's house. The friends of the couple come to spend the day with them in separate rooms in their parent’s house. This event is called karikompe.

The newly married couple has advisors. The man’s advisor is called the 「khoussoumanta-yougo」 and the woman’s is called 「khoussoumanta-yakhare」. After one week of celebration, the women meet to show the gifts that the couple received from their parents mostly from the woman's mother.[1]

割禮[編輯]

索寧克人實行割禮並把它叫做birou。村子裏的要人選定舉行割禮的日期,在割禮之前的幾個星期要舉行慶典。[需要解釋]

Festivities are organized during many weeks before from the date of circumcision has been chosen by the notables of the village.[需要解釋] Every afternoon, the boys who were circumcised the previous year organize tam-tams[需要解釋] for the new boys in order to prepare them psychologically. Throughout the circumcision ceremony, the boys to be circumcised sit around the 「tambour」 called 「daïné」. The other teenagers of the village, young girls, women, men and slaves form a circle.[需要解釋] During this time the boys surrounded with beautiful scarves disa sing.[2] The author Mamadou Soumare wrote 「Above its traditional surgery, the ritual of circumcision makes in evidence, the physical endurance, the pain, the courage, in one word the personality of the child.」

飲食[編輯]

索寧克人有着種類豐富的食物。例如,早餐包括「fonde(一種由小米、糖、牛奶和鹽做成的粥)」和「Sombi(大米、小米或玉米做的粥)」。午餐則是「demba tere」和「takhaya」,這兩種食物很常見,裏面有大米和花生,有時候還有Soninke的大雜燴——「Dere」,一種把小米和豆子燉着吃的混合物。[3]

經濟[編輯]

傳統上,索寧克人參與貿易和農耕。雨季里,男女都參與耕作。但是婦女通常留在家裏做飯和照顧孩子,他們也干別的活,像是染羊毛材料。索寧克人傳統的顏色是靛青。索寧克人生活標準較高。外出務工在他們的生活中很重要。大部分時間,婦女、兒童和老人呆在家裏,年輕人則到附近的城市裏賺錢。20世紀60年代以來,法國的大部分西非移民都是索寧克人。[4]索寧克人仍然是岡比亞、塞內加爾和馬里這些國家的中流砥柱。歷史上他們都是販賣金子、鹽甚至鑽石的商人。

宗教[編輯]

作為古代加納帝國的遺產[來源請求] ,索寧克人仍然保留着伊斯蘭教的信仰。他們是西非最早一批改信伊斯蘭教的民族。

參見[編輯]

引用[編輯]

- ^ Culture Et Tradition. Soninkara.com. 2002 [2006-04-05].

- ^ The circumcision among Soninke. Soninkara.com. [2006-04-28].

- ^ Soninke Recipes. Soninkara.com. 2002 [2006-04-05].

- ^ Meadows, R. Darrell. Willing Migrants: Soninke Labor Diasporas, 1848-1960. Journal of Social History. 1999 [2006-04-28].

參考文獻[編輯]

- (英文) François Manchuelle, Origins of Black African Emigration to France : the Labor Migrations of the Soninke, 1948-1987, Santa Barbara, University of California, 1987 (Thèse)

- (法文) M. T. Abéla de la Rivière, Les Sarakolé et leur émigration vers la France, Paris, Université de Paris V, 1977 (Thèse de 3 cycle)

- (法文) Amadou Diallo, L』éducation en milieu sooninké dans le cercle de Bakel : 1850-1914, Dakar, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, 1994, 36 p. (Mémoire de DEA)

- (法文) Alain Gallay, « La poterie en pays Sarakolé (Mali, Afrique Occidentale) », Journal de la Société des Africanistes, Paris, CNRS, 1970, tome XL, n° 1, p. 7-84

- (法文) Joseph Kerharo, « La pharmacopée sénégalaise : note sur quelques traitements médicaux pratiqués par les Sarakolé du Cercle de Bakel », Bulletin et mémoires de la Faculté mixte de médecine et de pharmacie de Dakar, t. XII, 1964, p. 226-229

- (法文) Kanté Nianguiry, Contribution à la connaissance de la migration "soninké" en France, Paris, Université de Paris VIII, 1986, 726 p. (Thèse de 3 cycle)

- (法文) Michael Samuel, Les Migrations Soninke vers la France, Paris, Université de Paris. (Thèse de 3 cycle)

- (法文) Badoua Siguine, La tradition épique des forgerons soninké, Dakar, Université de Dakar, 198?, (Mémoire de Maîtrise)

- (法文) Badoua Siguine, Le surnaturel dans les contes soninké, Dakar, Université de Dakar, 1983, 215 p. (Mémoire de Maîtrise)

- (法文) Mahamet Timera, Les Soninké en France : d'un histoire à l'autre, Karthala, 1996, 244 p. ISBN 2-86537-701-6

- (法文) Louis Léon César Faidherbe, Vocabulaire d'environ 1,500 mots français avec leurs correspondents en ouolof de Saint-Louis, en poular (toucouleur) du Fouta, en soninké (sarakhollé) de Bakel, 1864, Saint-Louis, Imprimerie du Gouvernement, 1864, 70 p.

- (法文) Louis Léon César Faidherbe, Langues sénégalaises : wolof, arabe-hassania, soninké, sérère, notions grammaticales, vocabulaires et phrases, E. Leroux, 1887, 267 p.

- (法文) Christian Girier, Parlons soninké, l'Harmattan, Paris, 1996, ISBN 2-7384-3769-9

- (法文) Rhonda L. Hartell, Alphabets de langues africaines, Unesco et Summer Institute of Linguistics, Dakar, 1993 ;

- (法文) Direction de la promotion des langues nationales du Sénégal, Livret d'auto-formation en Soninké, éditions Kalaama-Edicef, 2001.

外部連結[編輯]

- (法文) Site of the commune of Diawara, Sénégal

- (法文) Soobe - Association culturelle de Soninké en Egypte

- (法文) Diaguily - Portail de Diaguily, ville soninké du sud de la Mauritanie

- (英文) Ethnologue - Soninké language at Ethnologue

- (法文) Soninkara.com - Portail de la communauté soninké

- (法文) Soninkara.org - Société et Culture Soninké - Soninké News

- (英文) Asawan.org - Soninke literature - free online library/bookstore