混搭文化

混搭文化(英語:Remix culture),又名讀寫文化(英語:Read-write culture)是鼓勵以結合或改編現有素材的方式來創作衍生及創新作品或工藝品的社會文化。[2][3]默認情況下,重新混合文化將允許改善,更改,整合或以其他方式重新混合版權所有者作品的工作。儘管在整個人類歷史上都是各個領域的藝術家的普遍做法,[4]但在過去的幾十年中,排他性版權限制的增長越來越多地受到寒蟬效應[5]限制。 作為回應,哈佛法學院教授勞倫斯·雷席格(Lawrence Lessig)認為混搭是人類創造力的理想概念,自2000年代初以來一直在奏效[6],致力於將混搭概念轉移到信息時代。Lessig於2001年創立了知識共享組織,該組織發布了知識共享許可協議作為再次啟用重新混合文化的工具,因為當前對知識產權採用的默認專有版權制度在法律上禁止重新混合。用於文化作品的混搭文化與早期的軟件運動自由及開放源代碼軟件有關,並受到其啟發,這鼓勵了軟件作品的重用和混搭。

簡介

[編輯]

2008年,勞倫斯·雷席格在其撰寫的書籍《Remix》中描述了「混搭文化」的概念。勞倫斯將20世紀的默認媒體文化與計算機技術術語的使用(讀/寫文化(RW)與只讀文化(RO))進行了比較。[5]

通常在只讀媒體文化中,該文化或多或少被消極地使用。[5]信息或產品由「專業」來源(內容行業)提供,該來源擁有對該特定產品/信息的授權。由於內容生產者和內容消費者之間的明確角色分離,因此創意內容和想法只有一種單向流動。模擬信號和複製技術的出現(數字化革命之前和諸如廣播電視之類的互聯網之類的技術)從本質上使反滲透文化的生產和發行業務模型成為可能,並限制了消費者對媒體消費的作用。

數字技術沒有它之前的模擬技術的「自然」約束。必須對反滲透文化進行重新編碼,以與互聯網使之成為可能的「免費」發行競爭。這主要以數字版權管理(DRM)的形式完成,它在使用上強加了任意限制。無論如何,事實證明,DRM在加強模擬媒體約束方面幾乎無效。[9][10]

讀/寫文化在生產者和消費者之間具有相互關係。以歌曲之類的作品進行私人收藏是RW文化的典範,RW文化在複製技術出現之前被認為是「大眾」文化。[5] 然而,不久之後的技術和版權法改變了流行文化的動力。隨着專業化的發展,人們被教導將生產推遲到專業人士手中。

數字技術為復興RW文化和使生產民主化提供了工具,有時也稱為Web 2.0。博客解釋了這種民主化的三個層面。博客允許訪問非專業的用戶生成內容,從而重新定義了我們與內容行業的關係。隨後的「評論」功能為讀者提供了與業餘撰稿人進行對話的空間。用戶根據內容對博客進行「標記」,為用戶提供了必要的層,以便用戶根據自己的興趣過濾內容。第三層添加了漫遊器,該漫遊器通過計算各個網站之間的點擊次數來分析各個網站之間的關係,從而組織了首選項數據庫。這三層工作共同建立了聲譽生態系統,可引導用戶進入博客空間。 儘管毫無疑問,許多業餘在線出版物都無法與專業資源的有效性競爭,但數字RW文化的民主化和聲譽生態系統提供了一個空間,可以讓人們聽到很多數字前RO模型所沒有的有才華的聲音。

媒體文化融和

[編輯]為了使混搭文化得以生存,它必須由他人共享和創造。這是 參與文化 發揮作用的地方,因為消費者開始成為貢獻者,尤其是在這些媒體文化中成長的許多青少年開始參與。[11] 亨利·詹姆斯(Henry·詹姆斯)於2013年出版了一本書,名為「閱讀參與性文化」,着重介紹了他將原著故事《白鯨》(Moby-Dick)混搭的技巧,從而為學生提供了一種全新的體驗。[12][13]這種教學形式加強了參與性文化與混音文化之間的相關性,同時突顯了其在不斷發展的文學中的重要性。由於媒體文化的消費者開始將藝術品和內容視為可以重新利用或重新創造的事物,因此使他們成為製作人。

對藝術家的影響

[編輯]混音文化創造了一個幾乎沒有藝術家擁有或擁有「原創作品」的環境。[14] 媒體和互聯網已經使藝術變得如此公開,以至於將其作品留作其他解釋,並以此作為回饋。模因是21世紀最主要的例子。 一旦一個人進入了信息空間,就自動假定其他人可以過來並重新混合圖像。[15] 例如,由畫家雷內·馬格利特(Rene Magritte)創作的1964年自畫像「 Le Fils De L'Homme」,由街頭藝術家羅恩·英格朗(Ron English)在他的作品「立體聲馬格利特」中進行了重新混合。[16]

無障礙服務的版權和混搭

[編輯]殘疾人服務技術可以豁免版權媒體的更改,以使其可以訪問。[17] 美國盲人基金會(AFB),美國盲人理事會(ACB)和Samuelson-Glushko技術法律與政策診所(TLPC)與美國版權局,國會圖書館合作,續簽了允許視障人士轉換的豁免條款受版權保護的視覺文字可用於電子閱讀器和其他形式的技術,從而使它們可以訪問。[18] 只要以合法方式獲得受版權保護的材料,該豁免允許對其進行重新混合,以幫助殘障人士使用。 [17] 只要以合法方式獲得受版權保護的材料,該豁免允許對其進行重新混合,以幫助殘障人士使用。 [19]擁有可以限制感知的任何殘疾人士獲得的適當許可,可以重新混合合法獲得的受版權保護的材料,以使他們理解。 [19] [20]它的上一次更新是在2012年,並且一直保持下去。 [17]

混搭領域

[編輯]傳統民族聲樂

[編輯]

- 民俗學早於任何版權法就已存在。在民間,所有民間故事,民間歌曲,民間藝術,民歌等都在不斷地被修改。拉姆齊·伍德拉姆齊·伍德(Ramsay Wood)認為,[23]最古老的混搭文化例子是五卷書,這是古印度人收集的經文和散文中相互聯繫的動物寓言,被安排在一個框架內。梵文的原始作品被認為是在公元前3世紀左右[21]編寫的,其基礎是較古老的口頭傳統,包括「動物的寓言如我們所能想象的那樣古老」。[22]在接下來的2300年裡,對Panchatantra進行了至少200次使用世界各地50種不同語言的重新解釋。[24][25][26]

- 烹飪食譜可能是人類最古老的知識之一,該知識被進一步繼承,並且不受限制地共享以適應和改進。最近的一個例子是Superflex的Free Beer項目,該項目的菜譜和標籤藝術品均受知識共享許可協議,並積極鼓勵人們自由改編和重複使用。

- 模仿是諷刺的一種形式,它通過調適另一件藝術品來嘲笑它。模仿至少可以追溯到古希臘時代。模仿藝術存在於所有藝術媒體中,包括文學,音樂和電影。

圖形化藝術

[編輯]- 圖形技術中的混音長期稱為挪用。圖形占用的一個例子是列奧納多·達·芬奇的作品《蒙娜麗莎》的無休止的混搭(請參閱《蒙娜麗莎》的複製品和重新解釋以及《蒙娜麗莎》的衍生作品)。這幅畫已被無數次複製,具有不同的面孔和Photoshop效果,例如馬塞爾·杜尚(Marcel Duchamp)的L.H.O.O.Q.。一些重新混合的圖像包括蒙娜麗莎(Mona Lisa)與戇豆先生混合的Photoshop圖像以及類似外星人的版本。

- 塗鴉是讀寫文化的一個示例,參與者在其中與周圍環境和環境互動。與廣告裝飾牆壁的方式幾乎相同,塗鴉使公眾可以選擇要在其建築物上顯示的圖像。通過使用噴漆或其他媒介,藝術家基本上可以重新混合併更改牆或其他表面以顯示其扭曲或批判。例如,班克斯是當代著名的英國塗鴉藝術家。

書籍和其他信息

[編輯]

- 維基百科是書面混搭的一個例子,鼓勵公眾在百科全書中增加他們的知識。基於Wiki的網站實質上允許用戶重新混合顯示的信息。 Amazon.com稱Wikipedia為「世界上最詳盡且最新的百科全書」,因為它是由如此眾多的人編輯和製作的。[27]

- 掃譯是粉絲將漫畫從一種語言翻譯成另一種語言的翻譯。

- 結合了多本書的書籍混搭在2009年引起了賽斯·葛雷恩·史密斯的《傲慢與偏見與殭屍》的關注。

- 開放街圖項目創建了一個免費的世界可編輯地圖,[28]擁有超過200萬註冊用戶,他們使用手動測量,GPS設備,航拍和其他免費資源收集數據。[29]

- Wikimedia Commons是數字數據存儲庫,開放供公眾免費提供內容。內容(主要是圖像和聲音文件)已根據頁面不存在的Creative Commons許可進行許可,可讓任何人免費重複使用和重新混合。另一個示例是協作圖像託管網站Flickr和Deviantart,它們提供知識共享許可選項。

- 互聯網前的公共領域1960年代和1970年代的軟件是作為輸入程序不斷進行共享,編輯和改進的軟件。自由及開放源代碼軟件運動可以看作是那些程序的一種後繼者。

- 在1990年代建立的自由及開放源代碼軟件中,反對「只讀」專有軟件,共享,分支和重用是開發模型的自然組成部分。例如,具有商業後代Android和ChromeOS的Linux操作系統是軟件「混合文化」的高度成功的結果。

- 面向Internet的軟件存儲庫的出現在2000年代極大地幫助了remix軟件開發模型。自2008年以來,GitHub一直以混音風格進一步促進了協作軟件開發,尤其是Web開發。

- Fangames是由粉絲們根據一種或多種既定的視頻遊戲製作的電子遊戲,通常在沒有正式續集的情況下充當續集。[30]Dōjin soft是日語特定的變體,並且通常用於專有硬件控制台的自製程序。

- OverClocked ReMix 是一個致力於數位圖書館的社區,該社區通過非商業性重新安排和重新詮釋歌曲來保存和向遊戲音樂音樂致敬。

- 遊戲模組改裝是已發布電子遊戲的創意改編。[31]在2000年代,視頻遊戲行業意識到了這一潛力,並經常通過改裝套件積極支持模組製造商。特殊情況包括非官方補丁,服務器仿真器和視頻遊戲的風扇翻譯,它們是由粉絲翻譯製造的,目的是減輕程序錯誤或缺點。[32]

- Machinimas 是通過視頻遊戲與視頻遊戲「混合」而成的粉絲製作的視頻,遠遠超出了最初的範圍和意圖。

- 模仿和逆向工程將逆向運算以及計算機和數位圖書館的活動描述為重新混合文化的各個方面。[33]

- 家用3D打印在很大程度上依賴於重新混合,因為這允許用戶重新利用現有設計。一些學術研究強調了重新混合對於3D打印社區的重要性。[34][35][36][37]Thingiverse是3D打印社區,它的用戶可以創建,共享和訪問各種可打印的數字模型。重新混合現有模型的可能性是該平台的核心。 2016年,微軟啟動了Remix3D.com,這也是一個致力於3D打印模型的社區。

音樂

[編輯]- DJ是將現場錄製的音樂資料重新編排和重新混音為新作品的行為。從這種音樂中,混音一詞傳播到其他領域。

- 安排涉及採用已經存在的旋律並將其重新概念化為新歌曲。術語「混音」通常在Internet連續性內使用,與該實踐同義,獨立於應用於音樂的術語「混音」的原始定義。[來源請求]

- 音樂製作中的採樣是重複使用和重新混合以製作新作品的一個示例。在嘻哈文化中,採樣廣泛流行。閃耀大師和Afrika Bambaataa是最早採用採樣方法的嘻哈音樂人。這種做法也可以追溯到諸如齊柏林飛船 (Led Zeppelin)之類的藝術家,他通過許多行為,包括威利·迪克森(Willie Dixon),切斯特·阿瑟·伯內特(Howlin'Wolf),傑克·福爾摩斯(Jake Holmes)和Spirit,對音樂的大部分進行插值。[38]通過截取一首現有歌曲的小片段,更改不同的參數(例如音高)並將其合併到新作品中,藝術家可以自己製作。

- 音樂混搭是現有音樂曲目的混合。 2004年的專輯dj BC野獸獲得好評[39][40],並在《新聞周刊》[41][42] 和《滾石》 [42]中得到了好評。第二張專輯名為Let It Beast,封面是漫畫家Josh Neufeld於2006年製作的。

在電影中,通常會進行混搭並以多種形式發生。

- 大多數新電影都是對漫畫,圖畫小說,書籍或其他形式媒體的改編。其他大多數好萊塢電影作品通常都是遵循嚴格的一般情節的流派電影。[43]這些形式的電影幾乎沒有原創性和創意性,而是依靠改編先前作品或流派公式中的材料。一個很好的例子是電影《殺死比爾》,該電影借鑑了其他電影中的許多技術和場景模板(前提是所有這些電影都是《豪勇七蛟龍》,這是七武士的官方翻拍,以及塞爾吉奧·利昂的《荒野大鏢客》。[44]

- 視頻混搭視頻混搭將彼此之間沒有可辨別關係的多個現有視頻源組合到一個統一的視頻中。混搭視頻的示例包括電影預告片混音,vids,YouTube Poop和supercut。[45] [46]

- 競爭是媒體粉絲文化的狂熱勞動實踐,即從一個或多個視覺媒體源的鏡頭中創建音樂視頻,從而以一種新的方式探索該源本身。動畫節目的專門形式稱為「動畫音樂錄像」,也由粉絲製作。

- 與DJ相似,VJing是通過技術中介對觀眾進行實時圖像處理,與音樂同步。[47]

- Fandub和Fansubs是發行的電影材料上的粉絲翻版。

- 華特·迪士尼的作品是重要的公司混音示例,例如《美女與野獸》,《阿拉丁》,《冰雪奇緣》。這些混音均基於較早的公有領域作品(儘管迪斯尼電影已從其原始來源進行了更改)。[48][49]勞倫斯·萊西格(Lawrence Lessig)因此將華特·迪士尼(Walt Disney)稱為「混搭師」,並稱讚他是2010年混音文化的理想選擇。[50]但是,一些記者報道說,迪士尼比以前更能容忍粉絲混搭(「粉絲繪圖」)。[51]

GIFs

[編輯]GIF是混音文化的另一個例子。它們是在線對話中用於個人表達的電影的插圖和小片段。[52] GIF通常是從在線視頻形式中獲取的,例如電影,電視或YouTube視頻。[53]每個剪輯通常持續約3秒鐘[54],並「循環,擴展和重複」。[54] GIF會從大眾語境中獲取大眾媒體樣本並對其影像進行重新想象或重新混合,以將其用作個人形式在不同上下文中的表達。[55]它們在各種媒體平台上都得到使用,但在Tumblr中最流行,用於表達清晰的線條。[54]

宗教混合

[編輯]在整個歷史中,混合文化不僅在交流口頭故事方面而且在聖經中都是真實的。[56]尤金·畢德生(Eugene H. Peterson)在他的2002年出版的《消息//重新混音》一書中重新解釋了聖經的故事,這使聖經更易於讀者理解。[57]混音的想法可以追溯到貴格會(Quakers),後者會用自己的聲音來解釋聖經並創造聖經的敘述,這與更普遍的「只讀」做法背道而馳。[58]

歷史

[編輯]混搭一直是人類文化的一部分。[4]美國媒體學者亨利·詹金斯(Henry Jenkins)教授辯稱,「也許可以通過混合,匹配和融合來自不同土著和移民人群的民間傳統來講述19世紀美國藝術的故事。」混搭的另一個歷史例子是Cento,一種在歐洲中世紀流行的文學體裁,主要由直接從其他作者的作品中借來的經文或摘錄構成,並以新的形式或順序排列。[4]

創造和消費之間的平衡隨着媒體記錄和再現技術的進步而發生了變化。值得注意的事件是圖書印刷機的發明和模擬錄音和複製,從而導致了嚴重的文化和法律變化。

模擬時代

[編輯]專用的昂貴的創建設備(「讀寫」)和專用的廉價消費(「只讀」)設備允許少數幾個人集中生產,而很多人分散消費。面向消費者的低價格,缺乏書寫和創建能力的模擬設備迅速普及:報紙,

在20世紀初,模擬時代開始錄音和複製革命。約翰·菲利普·蘇薩,晚期浪漫時代的美國作曲家和指揮,在1906年的國會聽證會上警告如今出現的「罐裝音樂」對音樂文化產生了負面變化。[59][60]

這些說話的機器將會破壞這個國家音樂的藝術發展。當我還是個男孩的時候……在夏天的夜晚,在每所房子前面,你會發現年輕人一起唱歌或今天的老歌。今天您聽到這些地獄機器晝夜不停地運轉,我們將不再有聲帶。聲帶將通過進化的過程被消除,就像尾巴的尾巴一樣。他是從猿猴那裡來的。

自動點膠機,廣播,電視。這種新的商業模式,即工業信息經濟,要求並導致整個19世紀和20世紀加強專有版權,削弱了混音文化和公共領域。

模擬創建設備價格昂貴,並且其編輯和重新排列功能也受到限制。由於質量不斷惡化,作品(例如磁帶錄音機)的模擬副本無法經常進行編輯,複製和處理。儘管如此,創造性的混音文化在一定程度上得以倖存。例如,作曲家John Oswald於1985年在他的隨筆《聲樂》中創造了聲樂術語,或將「音頻盜版」作為基於現有音頻記錄的聲音拼貼的合成特權,並以某種方式對其進行了更改以製作新的作品。

重新混合為數字時代現象

[編輯]

數字革命徹底改變了技術。[61]數字信息可以無限地複製和編輯,而通常不會造成質量損失。儘管如此,在1960年代,首批具有這種功能的數字通用計算設備僅面向專家和專業人員,而且價格昂貴。首批面向消費者的設備(如電子遊戲機)本質上缺乏RW功能。但是在1980年代,家用電腦,特別是IBM個人計算機的到來,以可承受的價格向大眾推出了數字生產者設備,該設備可同時用於生產和消費。[62][63] 與軟件類似,在1990年代,自由及開放源代碼軟件運動基於任何人的可編輯性思想實現了軟件生態系統。

互聯網和web 2.0

[編輯]互聯網在1990年代末和2000年代初的出現為在藝術,技術和社會的所有領域重新實現「混音文化」提供了一種非常有效的方法。與電視和廣播不同,Internet具有單向信息傳輸(從生產者到消費者),而互聯網本質上是雙向的,從而實現了對等動態。由於基於Commons的對等生產的可能性,Web 2.0和更多用戶生成內容加快了這一步。歌曲,視頻和照片的混音很容易分發和創建。對正在創建的內容進行了不斷的修訂,無論是專業規模還是業餘規模。 庫樂隊和Adobe Photoshop等各種面向最終用戶的軟件的可用性使混音變得容易。互聯網允許向公眾分發混音。網絡模因是特定於互聯網的創意內容,通過網絡及其用戶所進行的病毒傳播過程來創建,過濾和轉換。

知識共享基金會

[編輯]

為了應對更加嚴格的版權制度(Sonny Bono版權術語擴展,DMCA),該制度開始限制網絡的繁榮共享和重新混合活動,勞倫斯·雷席格於2001年創立了知識共享基金會。2002年,知識共享基金會發布了一套許可,作為允許重新混合文化的工具,通過允許平衡,公平地發布創意作品來「保留某些權利」,而不是通常的「保留所有權利」。在接下來的幾年中,一些公司和政府組織採用了這種方法和許可證,例如Flickr,DeviantART [64]和Europeana使用或提供允許重新混合的CC許可證選項。有許多網頁介紹了這種混音文化,例如ccMixter成立於2004年。

Brett GaylorRiP!: A Remix Manifesto發行的2008年開源電影記錄了「版權概念的變化」。[65][66]

2012年,加拿大的《版權現代化法案》明確添加了一項新的豁免條款,允許進行非商業混音。[67] 2013年,美國法院對Lenz v. Universal Music Corp.的判決承認,業餘混搭可能屬於合理使用範圍,因此要求版權所有者在進行數字千年版權法案(DMCA)刪除通知之前,請檢查並尊重合理使用。[68]

版權

[編輯]根據許多國家/地區的版權法,任何有意對現有作品進行混音的人都應對法律訴訟負責,因為法律保護了作品的知識產權。然而,事實證明,當前的版權法在防止內容採樣方面無效。[69][70]另一方面,合理使用不能解決足夠廣泛的用例,其邊界也沒有得到很好的確定和定義,這使得「合理使用」下的使用具有法律風險。 Lessig認為,要使混音文化合法化,就需要對當前的版權法進行修改,尤其是在合理使用的情況下。他指出,「過時的版權法已將我們的孩子變成罪犯。」[71] 一種主張是採用與書目引用一起使用的引文系統。藝術家會引用她所採樣的知識產權,這會給原始創作者以功勞,這在參考文獻中很常見。作為實現此目的的工具,勞倫斯·萊西格(Lawrence Lessig)提出了的創用CC許可,該許可要求例如出處,而不限制創作作品的一般使用。進一步的措施是自由內容運動,該運動建議應在免費許可下發布創意內容。正如學者魯弗斯·波洛克(Rufus Pollock)辯論的那樣,版權改革運動試圖通過削減例如過長的版權條款來解決該問題。[72][73]

其他版權學者,例如Yochai Benkler和Erez Reuveni [74]提出了與混音文化密切相關的想法。一些學者認為,學術和法律制度必須隨着文化的變化而朝着基於混音的文化發展。[75]

影響

[編輯]2010年2月,卡托研究所的Julian Sanchez對混音活動能夠顯示社會價值表示而讚賞,並指出應就「允許對我們的社會現實行使的控制水平」對這種活動進行版權進行評估。[76][77]

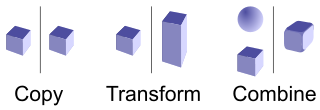

根據Kirby Ferguson在2011年和他受歡迎的TED大會所說[79],一切都是重新混合,並且所有原始材料都是基於先前存在的材料進行重新混合而成的。[80]]他認為,如果所有知識產權都受到其他作品的影響,那麼版權法就沒有必要了。弗格森(Ferguson)表示,創造力的三個關鍵要素-複製,轉化和結合-是所有原始創意的基礎。以巴勃羅·畢卡索(Pablo Picasso)的名言「優秀畫家複製,偉大畫家偷竊」為基礎。[78]

2015年6月,WIPO一篇題為「混音文化和業餘創造力:版權困境」的文章[68]承認「混音時代」和版權改革的必要性。

爭議

[編輯]混搭文化並無批評者,不過在抄襲指控方面嚴重。[81][82]

Web 2.0評論家Andrew Keen在其2006年出版的《Cult of the Amateur》中批評了自由和讀寫文化。[83]

2011年,加利福尼亞大學戴維斯分校教授Thomas W. Joo批評混搭文化自由文化過於浪漫化。[84]特里·哈特(Terry Hart)在2012年曾提出過類似的批評。[85]

參見

[編輯]參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ downloads (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on creativecommons.org "The building blocks icon used to represent 「to remix」 is derived from the FreeCulture.org logo."

- ^ Remixing Culture And Why The Art Of The Mash-Up Matters (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on Crunch Network by Ben Murray (Mar 22, 2015)

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. Everything Is A Remix. [2011-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2011-04-27).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rostama, Guilda. Remix Culture and Amateur Creativity: A Copyright Dilemma. WIPO. 2015-06-01 [2016-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-23).

Most cultures around the world have evolved through the mixing and merging of different cultural expressions.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Larry Lessig. Larry Lessig says the law is strangling creativity. TEDx. ted.com. 2007-03-01 [2016-02-26]. (原始內容存檔於2016-02-17) (英語).

- ^ School, Harvard Law. Lawrence Lessig | Harvard Law School. hls.harvard.edu. [2018-11-25]. (原始內容存檔於2018-11-16) (英語).

- ^ Remix (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on lessig.org

- ^ Download Lessig’s Remix, Then Remix It (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on wired.com (May 2009)

- ^ A New Deal for Copyright (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on Locus Magazine by Cory Doctorow (2015)

- ^ The Role of Scientific and Technical Data and Information in the Public Domain: Proceedings of a Symposium. on National Academies Press (US); 15. The Challenge of Digital Rights Management Technologies by Julie Cohen (2003)

- ^ 57% of Teen Internet Users Create, Remix or Share Content Online. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2005-11-02 [2016-11-26]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-28) (英語).

- ^ There She Blows! Reading in a Participatory Culture and Flows of Reading Launch Today. henryjenkins.org. [2016-11-27]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-28).

- ^ Jenkins, Henry; Kelley, Wyn; Clinton, Katie; McWilliams, Jenna; Pitts-Wiley, Ricardo. Reading in a Participatory Culture: Remixing Moby-Dick in the English Classroom. Teachers College Press. 2013-01-01. ISBN 9780807754016 (英語).

- ^ maddysulla. Remix Culture: Its Own Art Form or the Death of Creativity?. Digital Media & Cyberculture. 2014-04-07 [2016-11-27]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-28) (英語).

- ^ Memes in Digital Culture (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Limor Shifman published by MIT Press (2012)

- ^ Remixed Masterpieces: When Artists Pay Homage to Other Artists. Flavorwire. 2011-07-07 [2016-12-09]. (原始內容存檔於2016-12-20) (美國英語).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Chapdelaine, Pascale. The Nature and Function of Exceptions to Copyright Infringement. Oxford Scholarship Online. 2017-11-23, 1. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198754794.003.0003.

- ^ Crombie, David; Lenoir, Roger, Designing Accessible Music Software for Print Impaired People, Assistive Technology for Visually Impaired and Blind People (Springer London), 2008: 581–613, ISBN 9781846288661, doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-867-8_16

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Office, U.S. Copyright. Chapter 1 - Circular 92 | U.S. Copyright Office. www.copyright.gov. [2018-11-25]. (原始內容存檔於2017-12-25) (英語).

- ^ Office, U.S. Copyright. Chapter 1 - Circular 92 | U.S. Copyright Office. www.copyright.gov. [2018-11-25]. (原始內容存檔於2017-12-25) (英語).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Jacobs 1888, Introduction, page xv; Ryder 1925, Translator's introduction, quoting Hertel: "the original work was composed in Kashmir, about 200 B.C. At this date, however, many of the individual stories were already ancient."

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Doris Lessing, Problems, Myths and Stories (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館), London: Institute for Cultural Research Monograph Series No. 36, 1999, p 13

- ^ See page 262 of Kalila and Dimna, Selected fables of Bidpai [Vol 1], retold by Ramsay Wood, Knopf, New York, 1980; and the Afterword of Medina's 2011 Fables of Conflict and Intrigue (Vol 2)

- ^ Introduction (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館), Olivelle 2006, quoting Edgerton 1924.

- ^ Ryder 1925, Translator's introduction: "The Panchatantra contains the most widely known stories in the world. If it were further declared that the Panchatantra is the best collection of stories in the world, the assertion could hardly be disproved, and would probably command the assent of those possessing the knowledge for a judgment."

- ^ Edgerton 1924,第3頁. "reacht" and "workt" have been changed to conventional spelling: '"...there are recorded over two hundred different versions known to exist in more than fifty languages, and three-quarters of these languages are extra-Indian. As early as the eleventh century this work reached Europe, and before 1600 it existed in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Old Slavonic, Czech, and perhaps other Slavonic languages. Its range has extended from Java to Iceland... [In India,] it has been worked over and over again, expanded, abstracted, turned into verse, retold in prose, translated into medieval and modern vernaculars, and retranslated into Sanskrit. And most of the stories contained in it have "gone down" into the folklore of the story-loving Hindus, whence they reappear in the collections of oral tales gathered by modern students of folk-stories."

- ^ Kindle 3G Wireless Reading Device. 2010-08-04. (原始內容存檔於2010-08-04).

Wireless Access to Wikipedia Kindle also includes free built-in access to the world's most exhaustive and up-to-date encyclopedia, Wikipedia.org. With Kindle in hand, looking up people, places, events, and more has never been easier. It gives whole new meaning to the phrase walking encyclopedia.

- ^ Lardinois, Frederic. For the Love of Mapping Data. TechCrunch. 2014-08-09 [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2019-11-15).

- ^ Neis, Pascal; Zipf, Alexander, Analyzing the Contributor Activity of a Volunteered Geographic Information Project — the Case of OpenStreetMap, ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 2012, 1 (2): 146–165, Bibcode:2012IJGI....1..146N, doi:10.3390/ijgi1020146

- ^ Rainer Sigl. Lieblingsspiele 2.0: Die bewundernswerte Kunst der Fan-Remakes. Der Standard. 2015-02-01 [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-24).

- ^ Computer game mods, modders, modding, and the mod scene (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Walt Scacchi on First Monday Volume 15, Number 5 (3 May 2010)

- ^ You're in charge! - From vital patches to game cancellations, players are often intimately involved. (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Christian Donlan on Eurogamer "Supreme Commander fans released Forged Alliance Forever and gave the game the online client it could otherwise only dream of. I haven't played it much, but I still got a tear in my eye when I read about the extents these coders had gone to. There's nothing quite so wonderful to witness as love, and this is surely love of the very purest order. [...] SupCom guys resurrect a series whose publisher had just gone under." (2013-11-02)

- ^ Yuri Takhteyev, Quinn DuPont. Retrocomputing as Preservation and Remix (PDF). iConference 2013 Proceedings. 2013: 422–432 [2016-03-26]. doi:10.9776/13230 (不活躍 2019-10-31). (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2020-12-10).

This paper looks at the world of retrocomputing, a constellation of largely non-professional practices involving old computing technology. Retrocomputing includes many activities that can be seen as constituting 「preservation.」 At the same time, it is often transformative, producing assemblages that 「remix」 fragments from the past with newer elements or joining together historic components that were never combined before. While such 「remix」 may seem to undermine preservation, it allows for fragments of computing history to be reintegrated into a living, ongoing practice, contributing to preservation in a broader sense. The seemingly unorganized nature of retrocomputing assemblages also provides space for alternative 「situated knowledges」 and histories of computing, which can sometimes be quite sophisticated. Recognizing such alternative epistemologies paves the way for alternative approaches to preservation.

- ^ Friesike, S.; Flath, C.M.; Wirth, M.; Thiesse, F. Creativity and productivity in product design for additive manufacturing: Mechanisms and platform outcomes of remixing. Journal of Operations Management. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2018.10.004.

- ^ Flath, C.M.; Friesike, S.; Wirth, M.; Thiesse, F. Copy, transform, combine: exploring the remix as a form of innovation (PDF). Journal of Information Technology. 2017, 32 (4): 306–325 [2020-01-22]. doi:10.1057/s41265-017-0043-9. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2018-07-22).

- ^ Kyriakou, H.; Nickerson, J.V.; Sabnis, G. Knowledge Reuse for Customization: Metamodels in an Open Design Community for 3D Printing. MIS Quarterly. 2017, 41 (1): 315–332. Bibcode:2017arXiv170208072K. arXiv:1702.08072

. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.17.

. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.17.

- ^ Stanko, M.A. Toward a theory of remixing in online innovation communities. Information Systems Research. 2016, 27 (4): 773–791. doi:10.1287/isre.2016.0650.

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. Everything's A Remix. [2011-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2011-06-26).

- ^ The sound of surprise: Looking for Boston's best. Boston Phoenix. [2008-05-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).

- ^ Best (and worst) music of 2004. [2008-05-22]. (原始內容存檔於2008-04-29).

- ^ N'Gai Croal. Time for your mash-up?. Newsweek. 2006-03-06 [2008-05-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).

- ^ Brian Hiatt. Mash-up corner. Rolling Stone. [2008-05-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. Everything's A Remix Part 2. Everything's A Remix. [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2019-11-14).

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. Kill Bill Extended Look. Everything's A Remix. [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-01).

- ^ In the matter of exemption to prohibition on circumvention of copyright protection systems for access control technologies (PDF). Electronic Frontier Foundation. [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-09-12).

- ^ Tech Diary: Video Mashups — a New Kind of Art. 2011-08-04 [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2018-11-22).

- ^ "VJ: an artist who creates and mixes video live and in synchronization to music". - Eskandar, p.1.

- ^ 50 Disney Movies Based On The Public Domain (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on forbes.com (2014)

- ^ How Mickey Mouse Evades the Public Domain (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on priceonomics.com (Jan 7, 2016)

- ^ Lawrence Lessig. Re-examining the remix (video). TEDxNYED. ted.com. 2010-04-01 [2016-02-27]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-05).

Time 9:30: "This man (Walt Disney) is a Remixer extraordinaire, he is the celebration and ideal of exactly this kind of creativity."

- ^ How Disney learned to stop worrying and love copyright infringement (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on salon.com by Andrew Leonard (2014)

- ^ Huber, Linda. Culture & the reaction GIF. Gnovis. 2015 [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2019-01-01) –透過Georgetown University.

- ^ McKay, Sally. Affect of Animated GIFs. Art & Education. 2005 [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-06-11).

- ^ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Kanai, Akane. Jennifer Lawrence, Remixed: Approaching Celebrity Through DIY Digital Culture. Celebrity Studies. 2015, 6 (3): 322–340. doi:10.1080/19392397.2015.1062644.

- ^ Angelan. Digital Gesture: Rediscovering Cinematic Movement Through GIF. Refractory. 2012-12-29 [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-10).

- ^ The Bible is Fiction: A Collection Of Evidence. danielmiessler.com. 2007-05-13 [2016-12-09]. (原始內容存檔於2017-04-16) (美國英語).

- ^ The Message (MSG) - Version Information - BibleGateway.com. biblegateway.com. [2016-12-09]. (原始內容存檔於2016-10-18).

- ^ Wess, Author. Remix Culture and the Church. Gathering In Light. 2011-03-04 [2016-12-09]. (原始內容存檔於2016-12-20).

- ^ Berley,Paul Edmund,「約翰·菲利普·索薩的不可思議的樂隊」。 伊利諾伊大學出版社,2006年。第82頁。

- ^ Lawrence Lessig,2008年,「混音:使藝術和商業在混合經濟中蓬勃發展」,倫敦:Bloomsbury Academic 。第1章:「這些說話器將破壞這個國家音樂的藝術發展。當我還是個男孩的時候……在夏天的夜晚,在每所房子前面,你會發現年輕人在一起唱着白天的歌或老歌,今天你聽到這些晝夜運轉的地獄機器,我們將不再有聲帶。聲帶將通過進化的過程被消除,就像過去一樣。當他從猿類身上出來時,他的尾巴。」

- ^ Rostama, Guilda. Remix Culture and Amateur Creativity: A Copyright Dilemma. WIPO. 2015-06-01 [2016-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-23).

In a further twist, widespread access to ever more sophisticated computers and other digital media over the past two decades has fostered the re-emergence of a 「read-write」 culture.

- ^ The Coming War on General Computation (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) at 28C3 by Cory Doctorow (2011-12-30)

- ^ Prosumption (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by pineight.com

- ^ deviantArt - Creative Commons. 2008-06-23 [2016-07-19]. (原始內容存檔於2016-12-20).

- ^ Kirsner, Scott. "CinemaTech Filmmaker Q&A: Brett Gaylor of Open Source Cinema". (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) on CinemaTech

- ^ Sinnott, Shane. "The Load-Down 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2007-06-30.", Montreal Mirror, 2007-03-29. Accessed 2008-06-30

- ^ Rostama, Guilda. Remix Culture and Amateur Creativity: A Copyright Dilemma. WIPO. 2015-06-01 [2016-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-23).

Canada is one of a few countries, if not the only one, to have introduced into its copyright law a new exception for non-commercial user-generated content. Article 29 of Canada’s Copyright Modernization Act (2012) states that there is no infringement if: (i) the use is done solely for non-commercial purpose; (ii) the original source is mentioned; (iii) the individual has reasonable ground to believe that he or she is not infringing copyright; and (iv) the remix does not have a 「substantial adverse effect」 on the exploitation of the existing work.

- ^ 68.0 68.1 Rostama, Guilda. Remix Culture and Amateur Creativity: A Copyright Dilemma. WIPO. 2015-06-01 [2016-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-23).

in 2013 a district court ruled that copyright owners do not have the right to simply take down content before undertaking a legal analysis to determine whether the remixed work could fall under fair use, a concept in US copyright law which permits limited use of copyrighted material without the need to obtain the right holder’s permission (US District Court, Stephanie Lenz v. Universal Music Corp., Universal Music Publishing Inc., and Universal Music Publishing Group, Case No. 5:07-cv-03783-JF, January 24, 2013).[...] Given the emergence of today’s 「remix」 culture, and the legal uncertainty surrounding remixes and mash-ups, the time would appear to be ripe for policy makers to take a new look at copyright law.

- ^ Johnsen, Andres. Good Copy, Bad Copy. [2011-04-14]. (原始內容存檔於2011-04-17).

- ^ Is Sampling Always Copyright Infringement? (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Tomasz Rychlicki and Adam Zieliński (November 2009)

- ^ Colbert, Steven. The Colbert Report- Lawrence Lessig. The Colbert Report. [2011-04-25]. (原始內容存檔於2011-09-05).

- ^ Rufus Pollock. Optimal copyright over time: Technological change and the stock of works (PDF). University of Cambridge. 2007-10-01 [2015-01-11]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2013-02-21).

The optimal level for copyright has been a matter for extensive debate over the last decade. Using a parsimonious theoretical model this paper contributes several new results of relevance to this debate. In particular we demonstrate that (a) optimal copyright is likely to fall as the production costs of 'originals' decline (for example as a result of digitization) (b) technological change which reduces costs of production may imply a decrease or a decrease in optimal levels of protection (this contrasts with a large number of commentators, particularly in the copyright industries, who have argued that such change necessitates increases in protection) (c) the optimal level of copyright will, in general, fall over time as the stock of work increases.

- ^ Rufus Pollock. Forever minus a day? Calculating optimal copyright term (PDF). University of Cambridge. 2009-06-15 [2015-01-11]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2013-01-12).

The optimal term of copyright has been a matter for extensive debate over the last decade. Based on a novel approach we derive an explicit formula which characterises the optimal term as a function of a few key and, most importantly, empirically-estimable parameters. Using existing data on recordings and books we obtain a point estimate of around 15 years for optimal copyright term with a 99% confidence interval extending up to 38 years. This is substantially shorter than any current copyright term and implies that existing terms are too long.

- ^ Erez Reuveni, "Authorship in the Age of the Conducer", Social Science Research Network, January 2007

- ^ Selber, Stuart. Plagiarism, Originality, Assemblage. Computers & Composition. December 2007, 24 (4): 375–403. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.368.2011

. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2007.08.003.

. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2007.08.003.

- ^ Julian Sanchez. Lawrence Lessig: Re-examining the remix (video). TEDxNYED. ted.com. 2010-04-01 [2016-02-27]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-05).

Time 7:14: "social remixes [...] for performing social realities"; 8:00 "copyright policies about [...] level of control permitted to be exercised over our social realities"

- ^ The Evolution of Remix Culture (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Julian Sanchez (2010-02-05)

- ^ 78.0 78.1 The Three Key Steps to Creativity: Copy, Transform, and Combine (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Eric Ravenscraft on lifehacker.com (2014-10-04)

- ^ 79.0 79.1 THOUGHTS ON REMIX CULTURE, COPYRIGHT, AND CREATIVITY (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Melanie Picard (August 6, 2013)

- ^ Ferguson, Kirby. Everything's A Remix. Everything Is A Remix Part 1. [2011-05-02]. (原始內容存檔於2011-06-26).

- ^ Against recreativity: Critics and artists are obsessed with remix culture-Slate. [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2019-12-14).

- ^ When a 'Remix' Is Plain Ole Plagiarism - The Atlantic. [2020-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2019-12-14).

- ^ Keen, Andrew (May 16, 2006). Web 2.0; The second generation of the Internet has arrived. It's worse than you think. (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) The Weekly Standard

- ^ Remix Without Romance (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) Connecticut Law Review Vol.44 by THOMAS W. JOO (December 2011)

- ^ Remix Without Romance: What Free Culture Gets Wrong (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Terry Hart (April 18, 2012)

外部連結

[編輯]- 視頻資源

- Total Recut (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館)

- Everything Is a Remix (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館)

- Remixthebook (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Mark Amerika

- Remix Theory (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) by Eduardo Navas

- RE/Mixed Media Festival